New publication: Ashmore Reef and the case of the disappearing sea snakes

A new Ecosystem Change Ecology team publication in Frontiers in Marine Science

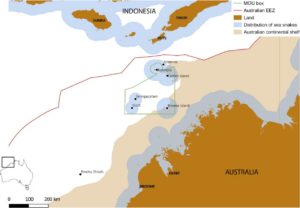

Figure 1: Location of Ashmore Reef in relation to other reefs and islands in the Timor sea.

As the global biodiversity crisis gathers pace, its reach into wild areas and distant islands becomes more common and increasingly pervasive. Issues such as climate change, loss of habitat, introduced species and pollution threaten these unique ecosystems. One of Australia’s most remote and isolated reefs (Figure 1), Ashmore Reef, which sits within the Ashmore Reef Marine Park, was once known as the global pinnacle of sea snake biodiversity.

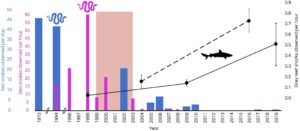

In the 200 years since the reef was observed by Captain Samuel Ashmore, western scientists have described 17 different species of sea snake living in the shallow waters. In the 1990’s it was estimated that around 40,000 sea snakes inhabited the remote reef. Yet in the early 2000s the once abundant sea snake fauna collapsed dramatically (Figure 2). This dramatic decline was not found to have happened anywhere else on surrounding reefs known to support sea snakes.

Understanding the reasons behind this biodiversity decline is the first step towards determining appropriate management responses. In a paper recently published in Frontiers in Marine Science, an international team of experts was brought together to sift through decades of past observations and draw on ecological theory to find an answer.

Figure 2: Trends in cumulative sighting rates of sea snakes (up to 17 species; blue and purple bars) and relative sighting rate of grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos; black points) at Ashmore Reef Marine Park

The Ecosystem Change Ecology team’s Dr Ruchira Somaweera, who led the detailed review, noted “We examined seven primary reasons for the disappearance of sea snakes from the shallow waters of Ashmore Reef. Despite narrowing down the cause to three possible explanations, a lack of information on this unique ecosystem means we still don’t have the answer.”

Figure 3: Evidence of predation of sea snakes by tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier).

“Increased vulnerability to pathogens due to extreme events, an increase in the number of sharks on the reef, and an increase in boat traffic are the issues that we have identified as priorities for further information gathering,” explained Dr Vinay Udawer, a research scientist at the Australian Institute for Marine Science and a senior collaborator on the work. “Our review outlines exactly what knowledge gaps need to be filled next if we are to address this wicked conservation challenge,” he notes.

“The case of the disappearing sea snakes at Ashmore Reef is an example of one of the many complex management questions we are tackling for both terrestrial and marine ecosystems at the reef,” remarked Dr Bruce Webber, one of the lead CSIRO scientists involved in the surveys at Ashmore Reef. “The Ashmore Reef Marine Park supports a remarkable ecosystem of considerable value. It is important that we not only take the time to find out why these dramatic changes in biodiversity have occurred, but that we also identify and implement solutions to restore and protect this iconic area for future generations.”

Read the paper here (open access): https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.658756